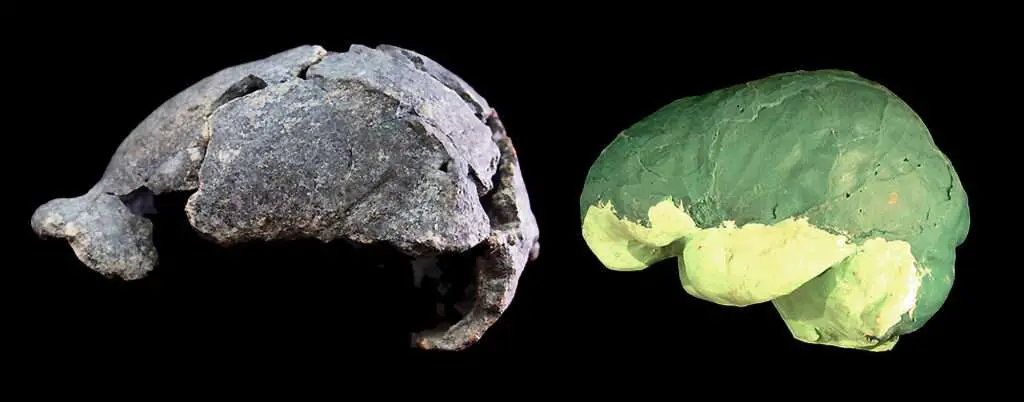

Experts have studied the skull of a 1.5 million-year-old human ancestor with one of the smallest cranial capacities and say that it was longer and rounder than those of modern humans.

Newsflash obtained a statement from the CENIEH (Centro Nacional de Investigacion sobre la Evolucion Humana; National Centre for Research on Human Evolution) dated 1st March saying that the experts studied the skull “of the Homo erectus fossil with the smallest cranial capacity”.

The statement explained how palaeoneurologist Emiliano Bruner and archaeologist Sileshi Semaw studied the 1.5 million-year-old skull, known as ‘DAN5/P1’, and said that their results suggest that its brain did “not present distinctive features of the human genus”.

The statement added: “CENIEH researchers published an article whose results suggest that its brain morphology does not present distinctive features of the human genus, having proportions similar to those of australopithecines or species whose evolutionary position – and belonging to our lineage – has yet to be established.”

The statement explained that the skull was found at the Ethiopian site of Gona and that its “cranial morphology indicates that it belongs to the species Homo erectus, and, in particular, to its first African stage, which is sometimes identified with the name Homo ergaster”.

Bruner said: “The DAN5/P1 skull is rounder and less elongated than is seen in later Homo erectus individuals, but this is likely due to skull architecture, rather than certain proportions of the cerebral cortex.”

The statement said: “This analysis confirms that evidence for a clear frontier for the origin of brain anatomy in humans is still lacking, at least in light of the current fossil record. Most of the differences between early human species – and even between humans and australopithecines – in brain anatomy are primarily associated with differences in the average size of the brain.

“The difficulty in finding brain features associated with the evolution of the genus Homo, beyond size, may be due to the absence of macroscopic differences in the cortex, to the limitations of the fossil samples, or to the difficulties when interfering. predict the morphology of the brain from the internal traces of the skull.”

Bruner added: “Of course, this does not exclude the possibility that the origin of the human brain may be associated with changes that cannot be detected in its general anatomy, such as changes that occur at the level of cells and tissues, of neural connections, or of neurotransmitters.”

The study was carried out in collaboration with Columbia University in New York City, Midwestern University in Glendale, Southern Connecticut State University in New Haven and the Stone Age Institute in Gosport, USA.

The findings have been published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology.