Gautam Adani, One of the top five richest persons in the world (https://www.bloomberg.com/billionaires/) who is pushing India into a potential new economic superpower, never delays taking crucial calls relating to his business.

“If he sees a crisis and a point of no return, he simply backs off and cuts off,” says a new book about the Indian billionaire.

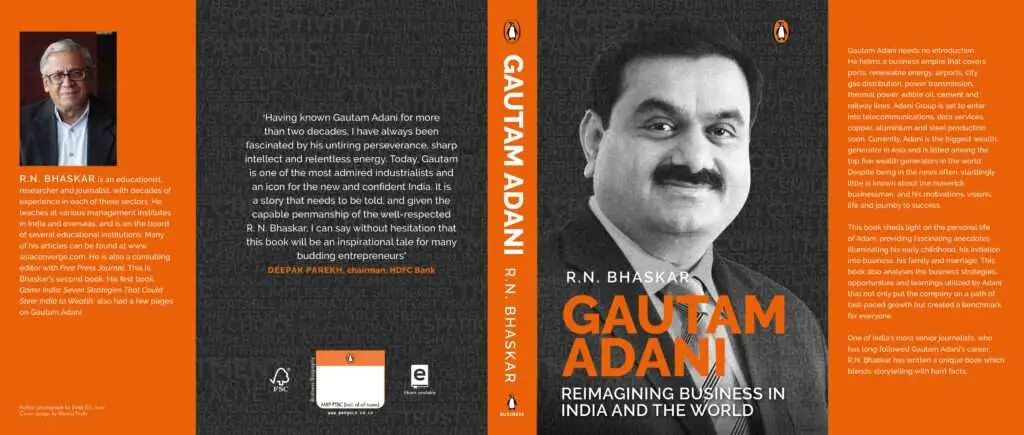

In short, Adani does not believe in the hop-skip-jump style of many South Asian tycoons, says the book, Gautam Adani: Reimagining Business In India And The World, penned by Mumbai-based editor and author, RN Bhaskar.

As of November 22, 2022, the only three people richer than Adani are Tesla boss Elon Musk with an estimated $251bn fortune, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos ($153bn) and Bernard Arnault ($136 bn).

Adani is on a high, says the book.

There is an interesting anecdote about the billionaire and his plans to develop the Mundra Port on India’s western coast, now owned by the Adani Group.

The international team of architects did some designs and put the cost at a whopping Rs 6000 crore plus, Adani nixed it within seconds and said he wanted a jetty to start with. His partners and family members were surprised. But work started and the first project – estimated at Rs 50-60 crore – paved way for the next, and the next and the next.

And within two and a half years, Mundra Port was ready in a record time.

This is not all.

When the jetty was being planned, Adani could not get dredgers from the state-owned Dredging Corporation of India. He asked for more cash from the bankers and bought some dredgers. He cleaned up the sea near Mundra, and now uses the dredgers – he has over 80 of them – for his own ports across India’s coastline. Why wait and delay a project? Why not buy a machine and speed up the project?, was his thinking.

The book explains Adani’s role in pushing business aggressively in a nation of 1.4 billion. The book says Adani, considered close to the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, would surely keep India on track to move into third place behind the US and China by 2030.

Enough has been written about the alleged political patronage to tarnish Adani’s image. In India, anyone close to the power is painted in black, critics conveniently forget that for generations, many industrial groups and their patriarchs, and their friends and their relatives grew only on the back of political influence instead of their competitiveness.

The big India economic growth story never found mention in Liz Truss’s gameplan (read blueprint) for a “modern brilliant Britain” but that never bothered Adani. He has his business empire firmly in place, Truss has lost her place and home and the UK has just been overtaken by India as the world’s fifth biggest economy. Thanks to him and another Indian billionaire Mukesh Ambani, the world today talks less of Chinese business tycoons like Alibaba founder Jack Ma.

The book says Adani, in particular, has come to represent India’s growing economic strength thanks to the rapid expansion of his Adani Group conglomerate, covering everything from ports to airports, and solar power to television. He became Asia’s richest in February and is now ranked fourth with a $123 billion fortune. The book says thanks to Adani, India has economic growth figures that were once the pride of Beijing.

The book narrates how Adani companies have benefited from economic liberalisation in the private sector, a rapidly growing working population, and the realignment of global supply chains away from China.

The tycoon has had strange brushes with all kinds of businesses, including diamonds. The book says Adani turned into a full-fledged diamond trader while in college and always had an overarching desire to strike big deals. He dropped out of college and told his relatives and friends that studies would never help him pursue his plans. “Gautambhai was resolute. Business first. Studies could come later,” someone says a terse, one liner in the book.

The book says Adani knows it by heart that the key part of India’s continued rise will be its ability to grow its manufacturing sector and challenge China as the world’s No 1 exporter.

The South Asian giant has already benefited from a large, well-educated, often English-speaking middle-class, helping the country to develop world-class IT and pharmaceutical sectors. And then, India has a strong consumer demand, which accounts for about 55% of the economy compared with less than 40% in China.

Adani’s conglomerate owns India’s largest private sector seaport and airport operator as well as coal mines in Indonesia and Australia. The company has faced fierce criticism for its environmental impact on the Great Barrier Reef as well as its use of billions of litres of water a year. But the book explains why Adani worked slowly on the Australian operations and silenced his critics, some of them operating from Dubai and feeding Indian newspapers and news channels unsubstantiated information on Adani group’s operations in Australia. Now, very few say Australia is the world’s largest thermal and metallurgy coal exporter. So why stop the Adani project, why carry placards during an India-Australia cricket match demanding a ban on the project?

It is legitimate coal mining, not blood diamonds from Congo or Sierra Leone. In Chhattisgarh where the group is routinely criticised, Adani is an operator, not an owner. It is a state government project and involves the governments of Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan.

Dustups over the Adani Group have often given opportunities to some to garner some cheap publicity. Consider this one. Once, the Nordik fund KLP told an international wire agency that it decided to divest from APSEZ due to the company’s links with the Myanmar military. Hilariously, KLP has invested only Rs 7 crore in this Indian company having a market cap of over 1.5 lakh crore and at least a dozen ports under its belt. Worse, the foriegn fund raised a brouhaha weeks after Adani Group announced its decision to abandon the Yangon International Terminal in Myanmar and earned headlines like never before.

Critics must know some more vital details of this project.

Adanis won the contract for the Yangon Project in 2019 when the democratically elected government of Myanmar was governing the country and the APSEZ had not paid any money to the new regime even before the coup started. Further, APSEZ announced its preparedness to write off the project, which accounted for 1.3% of its total assets. Strangely, no one asks KLP for its investments in other Western companies with interests in Myanmar.

It is about taking the right chance at the right moment for Adani, says the book.

Consider this one. When six Indian airports were lined up for privatisation in 2018, Indian PM Narendra Modi relaxed the rules to allow companies with no experience in running airports to bid for them. It was seen as a pathbreaking move and Adani’s company bought all six and became the country’s biggest airport operator.

There has been countless criticism about the debt figure of the Adani group at Rs 2.2 lakh crore. It looks massive at first sight and often triggers scary headlines.

But then, it is important to get a realistic view of the group’s real financial burden. The figures have to be seen in the context of areas where the group companies operate as well as their size and earnings. The areas from which the debt has been raised impact the cost of the debt, and hence, this becomes a factor to consider.

The book clears many such misconceptions about Adani.

The actual debt figure by itself needs to be clarified, as out of the Rs 2.2-lakh figure, there is Rs 0.35 lakh crore that represents loans from the promoters to various group entities, and Rs 0.21 lakh crore that is short-term debt balanced against receivables.

Now, looking at the nature of these two figures, the remaining debt figure comes down to Rs 1.64 lakh crore. This is a significant number. The other figure that is important here is the cash and cash equivalents on the books, which stand at around Rs 0.27 lakh crore. This means that the net debt actually stands at Rs 1.37 lakh crore.

Now this figure, when compared to various other companies in the infrastructure space, or even some other bigger companies in the manufacturing sector, is actually reasonable considering that it represents the figure of multiple companies operating across multiple sectors. The shifting focus of the group in terms of where the debt has come from is also significant. The notion that a large number of borrowings has been powered by banks and that, too, public sector banks, does not represent the actual situation.

Even more interesting is the break-up of the exposure of the total debt to banks. The share of banks is a total of around 40% in the debt. Within this, around 8 percent is that of global international banks, and another 11 percent is that of private sector banks. This leaves just the remaining 21 percent of the total borrowings, which have come from public sector banks. Quite clearly, the entire borrowing is diversified not only across different areas but even within the banking space, showing the extent and the depth of the banking relations of the group.

The book says Adani arrived on the scene at the right time. He had already laid a strong foundation in Gujarat through trading and private ports before “development” became the serious agenda in Indian politics. Many found his timing was right, and called him lucky. It was also the time when the Supreme Court compelled the government of India to end the unholy allocation era. Adani participated in auctions for renewable energy, airports, city gas distribution, road construction, development of transmission lines and even water management.

Adani’s aggressive bidding benefitted state and central governments immensely. The book says experts should study how the auction era has benefitted the end users with cheaper electricity, fuel and cost-effective timely power evacuation infrastructure. Adani Airport’s aggressive bidding for six airports will enrich the central government by hundreds of crores more compared to the offers made by cartels. But then, critics continue to call it a largesse of the BJP-led NDA government.

Time also favoured him when it came to inorganic growth. The book says Adani had a clean slate with banks, and it enabled him to buy strategic infrastructure assets through the resolution mechanism offered by NCLT. Indian and international financial institutions were and are happy to back Adani who has not disappointed the lenders. Those who follow the financial world know how the competitive world works. High level debts have never deterred investors across the world.

In short, the book explains what the group has done for the nation. The group currently employs about 20,000 directly and a couple of lakh indirectly. This is not a small figure.

It is a brilliant read.